A fellow shopper at Coober Pedy IGA solicits my attention

‘Can I ask, are you an Australia tourist or from overseas?’ He is mid turn down isle four. I wonder if he picked up on the energetic openness I just worked with my therapist to cultivate via videocall at the Coober Pedy basketball court. I can get a bit tunnel-visioned when I feel I have something to prove, a feeling I could reliably predict stepping into during my upcoming residency at Watch this Space.

‘Um…’ I equivocate, ‘…an Australian tourist, but I bought this hat here 7 years ago’, pointing to my baby-pink, fly-speckled broadbrim hat and simultaneously to the duration of my acquaintance with the town.

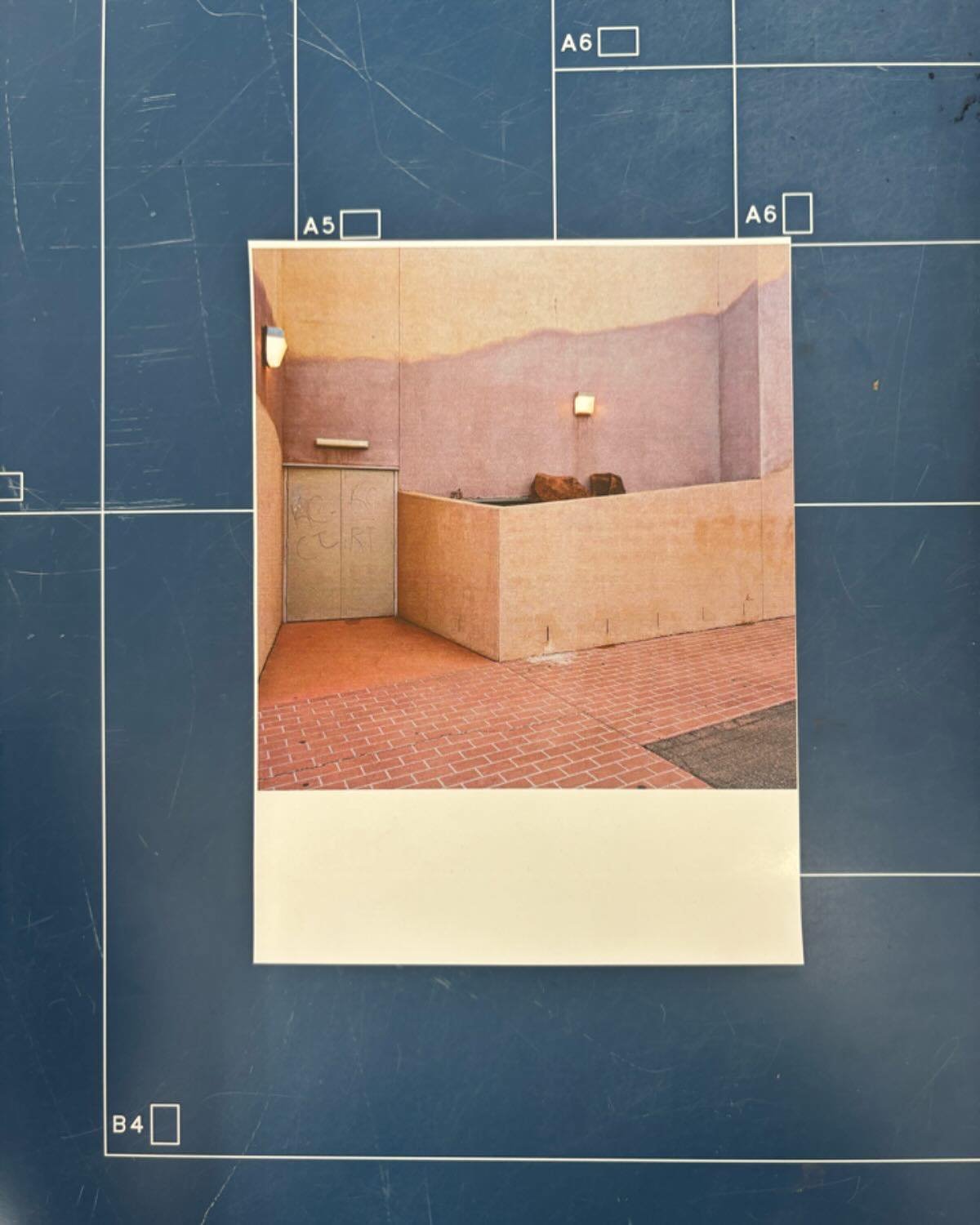

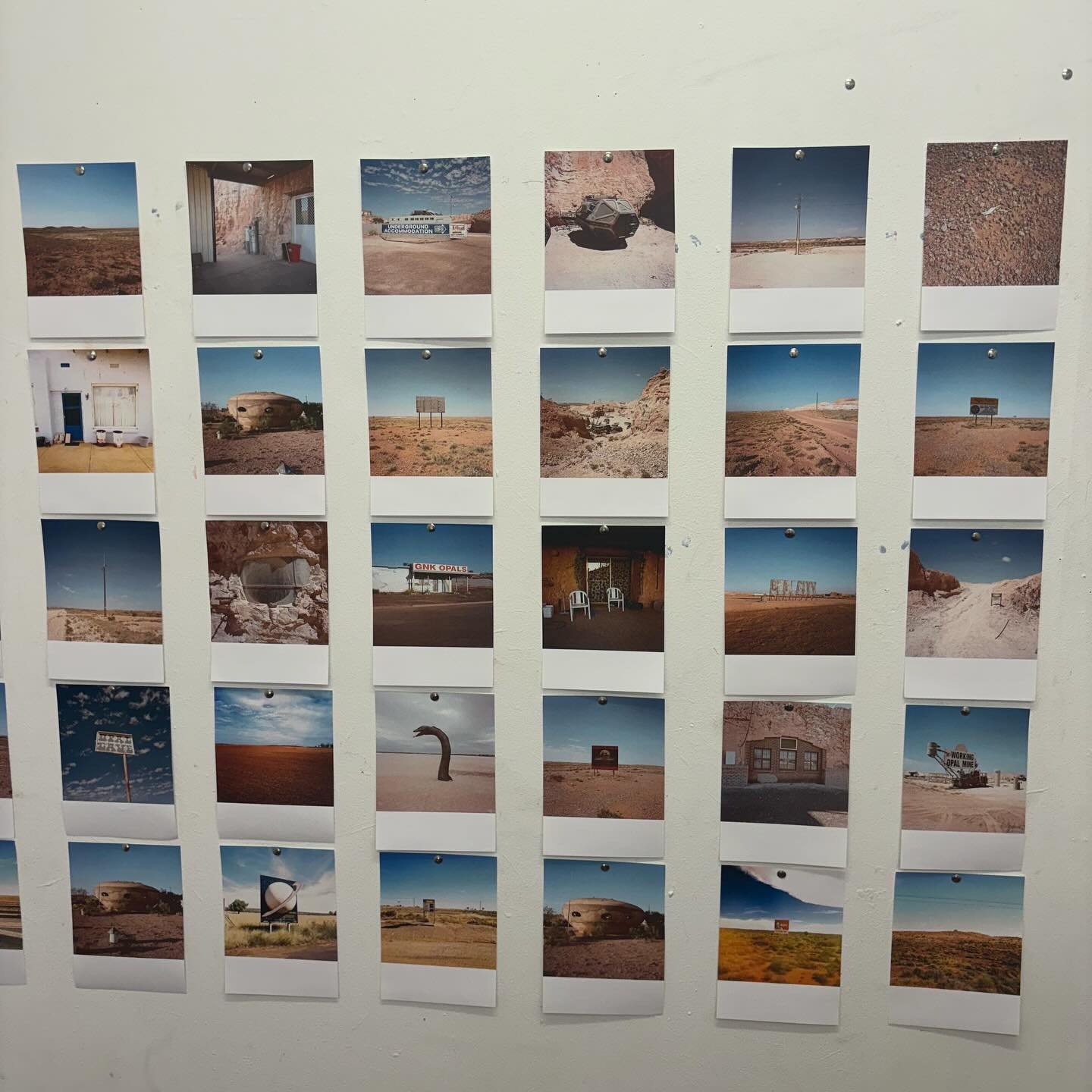

‘I’ve been here many times’ I clarify. The only other artist residency I’ve done in my life was here in this place, in 2021.

‘I believe you’ he says, ‘you look familiar, and once you come to Coober Pedy, it gets under your skin, you’ve just got to come back. I’m from Adelaide, but life is easier up here’.

I’m trying and failing to place his accent. Maybe German? Austrian? I’m terrible. Later on, my friend Serah says it was definitively Balkan, which adds up with what I understand of the migration patterns of the place. In fact, the very reason for our foray into the IGA is to buy a jar of ajvar for my friend Meret, not necessarily because it’s a rare delicacy, but because the stock selection of a supermarket indicates the cultural demographic of any given location. As much as supermarkets are intrinsically kinda evil by being a key player in the commodification of our subsistence, this little market barometer feels a bit sweet somehow.

Many people from former Yugoslavia were passing through Coober Pedy after having worked on the snowy hydro electrical scheme that was completed in the 70’s. They were on route to the next job – a big gold mine in Papua New Guinea – heading straight up the guts, as the expression goes, to get a boat from Darwin. But some got snared by the charm of the small opal mining town on the way.

‘So do you partake in opal fever?’ I ask.

‘Well, a little bit, I’m a scientist, atomic scientist’

‘Oh wow, and there’s work for you up here?’

‘Well… I have my own laboratory, but in the future, I will do different things, bigger things’

‘What kind of things?’ I probe, starting to feel like I am really probing. We had just been listening to a podcast on the open secret of Israel’s nuclear program as we pulled into Coober Pedy. At this point in the chat, old mate starts getting vague. He starts talking about opals, half-life, cobalt 13, how you can inject a bit more colour into the stones with radiation.

‘Like cancer’, he adds, indicating the lower level of radioactivity in the isotopes he was firing at the opals.

‘But isn’t all that… a bit… dangerous?’ I inquire, my concerns not quite allayed.

‘Well, sometimes you make mistakes’ he raises his right hand, his middle finger identifying itself by its stiff inertia. It’s as though all the digits have fused together.

I don’t really understand but I’ll ask Slumbi when we get back to the car which she is repacking while we get supplies. Born a month after Chernobyl blew, she seems to be infused with a deep nuclear curiosity, a correlation I insist on understanding as a confused fusion of vibes-based radioactive contamination and astrology-esque osmosis.

‘What’s your name?’ Old mate asks my friend Serah, who has just materialised behind me.

‘Serah’ she answers, in a demure demeanour.

At that point he fishes into his pocket and produces a plastic package, looks at me, then turns to Serah, perhaps deciding she needs to be won over, and hands her the small, cobalt blue opal. She hesitantly accepts. He invites us to his laboratory.

‘Maybe on the way back down?’ we ask each other, politely deferring his invitation. He proceeds to rifle through a small card holder, asking if we have facebook. He hands us a small rectangle of printing paper with artifacts of an invoice. His facebook URL scrawled in purple pen on one side, his PO Box printed on the other. We part ways.

‘I wonder if I should have accepted that opal…’ Serah ponders as we walk down aisle six, looking for salt and vinegar chips.

‘Because of its probable radioactive qualities?’

‘Yeah that too, but also I don’t accept stones from strangers as a general rule’

“Ah yes, I’ve heard my fair share of stories about crystals being used as portals…’ at that moment my attention is redirected by brand loyalty.

‘SAMBOYS!’ South Australia seems to be the stronghold for this brand of chip that once held hegemony in the school tuck shop.

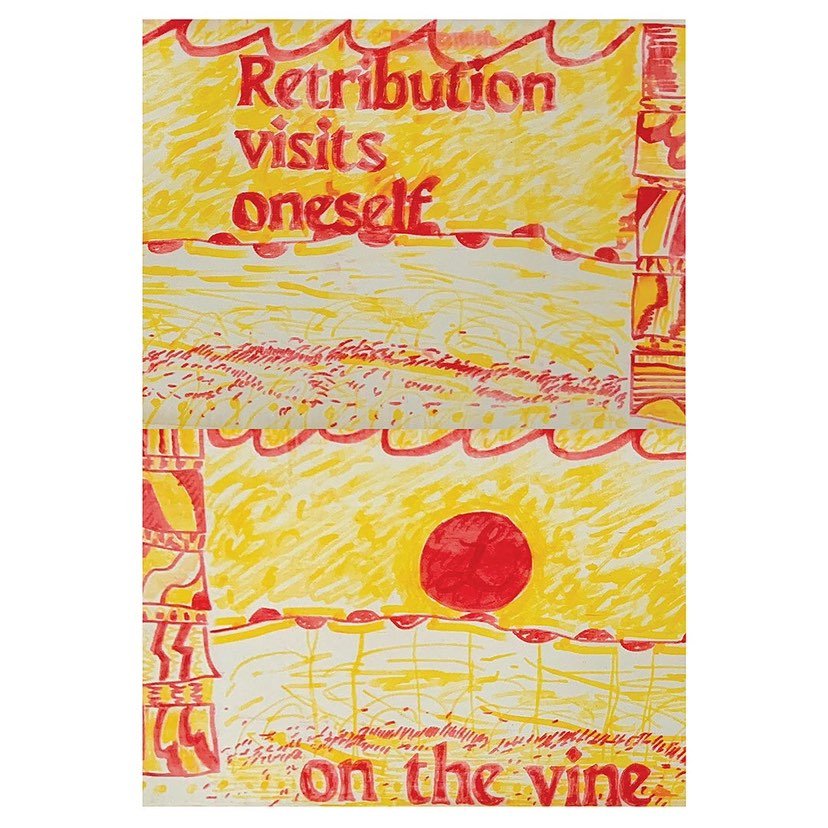

‘Atomic Tomato? Really?!’

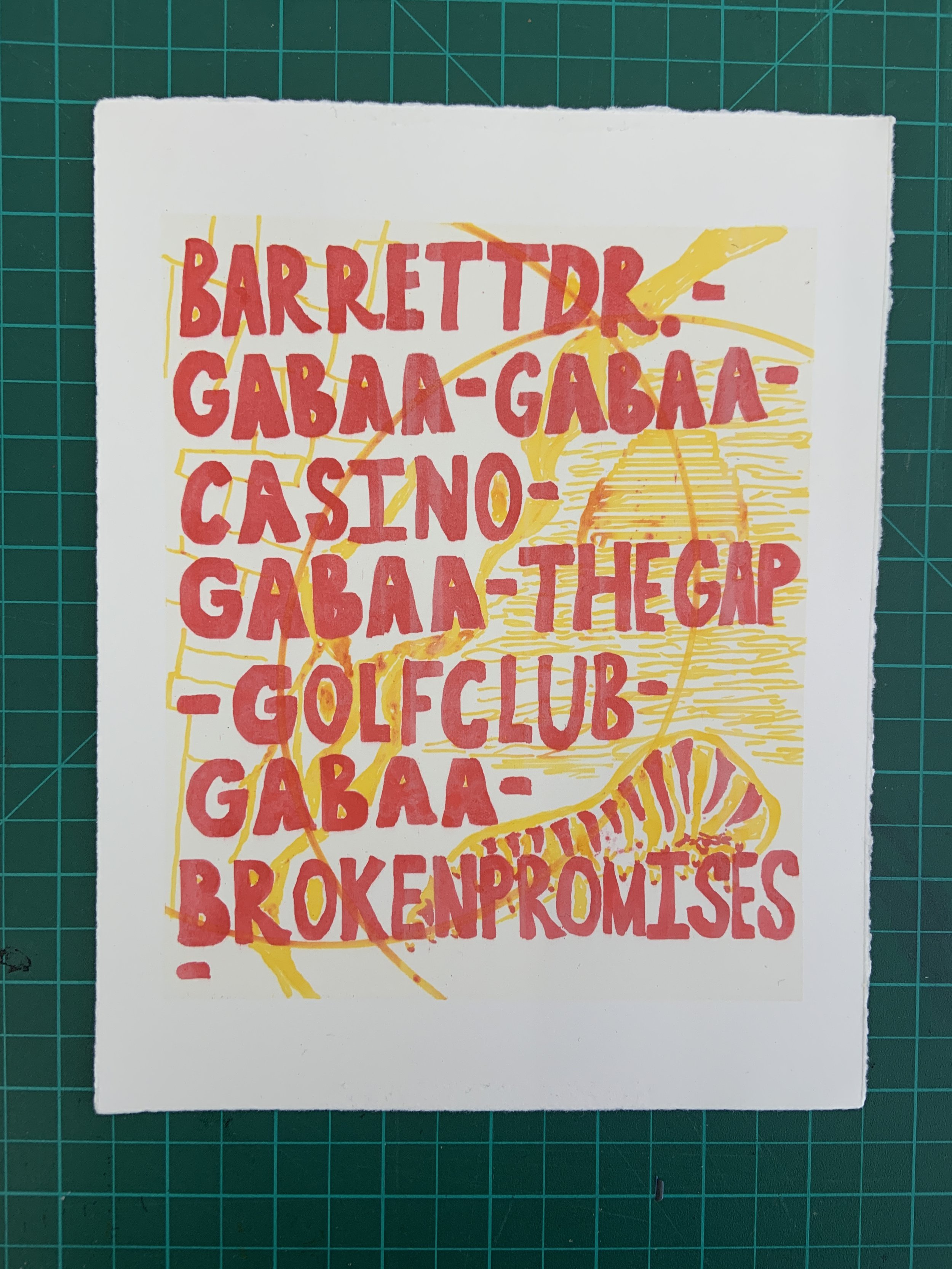

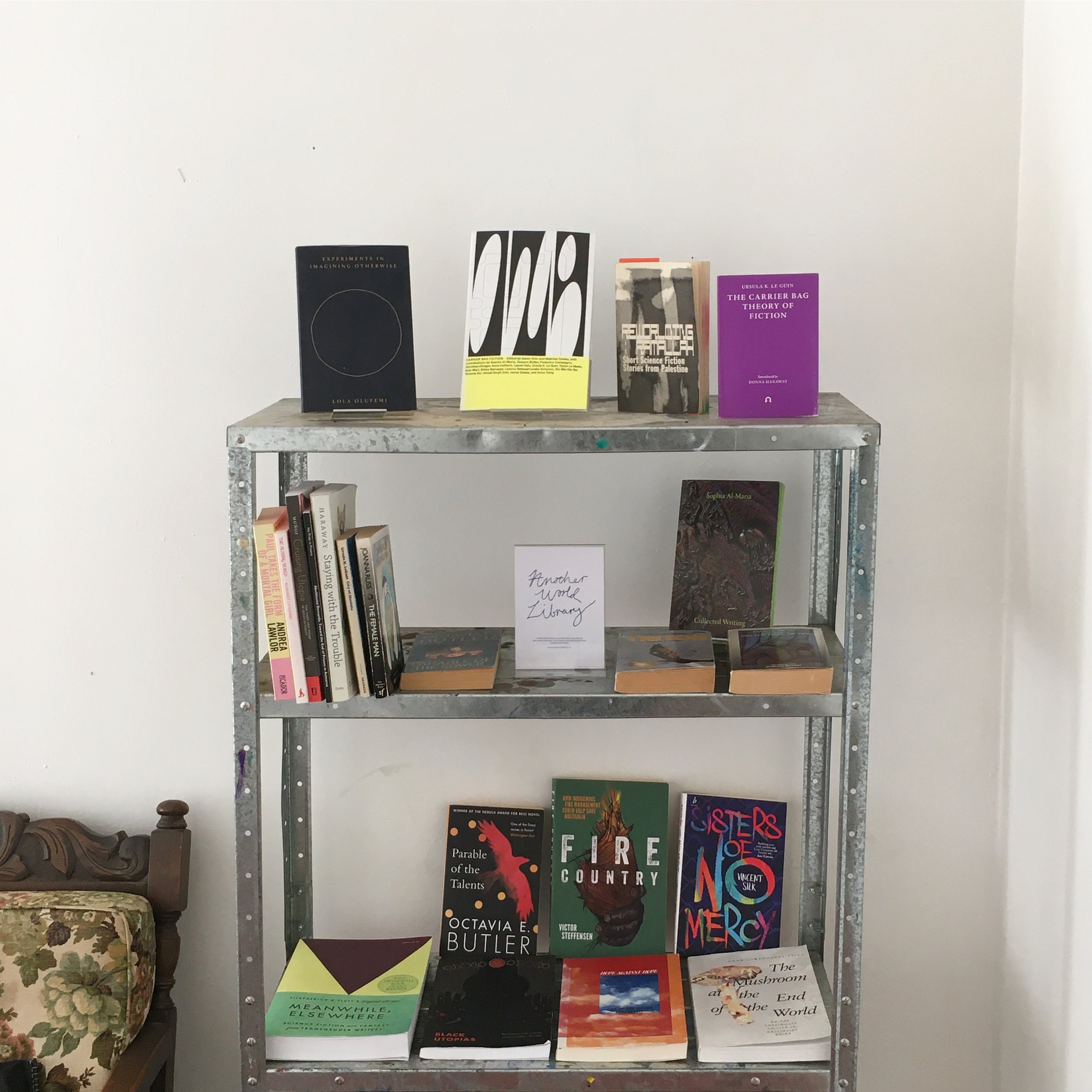

When we hit the road again, we start listening to an audiobook. My Seditious Heart by Arundhati Roy. The first chapter happens to be about nuclear weapons and deterrence, this time in the Pakistani/ Indian context. It’s become a bit of a theme on the road trip. Not only because we camped the night at Lake Hart rest stop, just within the southern perimeter of Woomera Prohibited Area, a section of land that was subject to British nuclear testing in the 50’s and 60’s (don’t harvest the salt) – a section of land approximately the size of North Korea spanning Kokatha, Arabana, Yankunytjara and Antakarinja country. But also because we were passing through Coober Pedy during what came to be known as the 12-day war between Israel and Iran, just a few days shy of the US dropping 14 bunker buster bombs, that’s 420,000 pounds of munition, on key Iranian nuclear facilities. Gets you thinking about how imperialism reproduces itself.

It felt like a sample of the atomic panic I’ve heard my parents talk about experiencing towards the end of the cold war. Only in this case Iran doesn’t have nuclear weapons, and Israel has heaps. We don’t know how many exactly because they haven’t had an inspection since the mock inspection in the early 60’s, we learnt in the first podcast I mentioned. Because of this they are not party to any non-proliferation or no-first-use treaty. The podcast detailed the pretend sites they built as a decoy, going to great extents to simulate a feeling of aged disuse (sprinkling bird poop in certain rooms, for example). Then LBJ got into power and didn’t continue with JFK’s mild badgering. Some put this badgering forward as the reason he was assassinated. I’ve heard many alternate theories. Something about a gold mine in West Papua as well. I haven’t bothered to formulate allegiance to any such theory. I get resentful about how central American political history is. Often the resentment of the actuality of that centrality outweighs its saturation of culture and curriculum, and I do myself some digging. I decide I first need to develop a position on why the 21st Prime Minister of Australia, Gough Whitlam, was dismissed. Was the CIA really involved? Was it because he threatened to close Pine Gap? Yes, I should develop a position on this first, I decide, as a way to scaffold my priorities.

In the car Serah gives me the opal and I put it in the empty Atomic Tomato packet for safe keeping. ‘Don’t throw this out’ I announce to the car, as it dawns on me that an empty chip packet is probably not the ideal location for safe keeping. But I want to keep the two artifacts of the experience together, maybe make a sculpture or something. Down the track, once in Alice and underway with the making, I realise the atomic tomato packet is AWAL. The cobalt blue opal, however, mysteriously turns up in the centre consol.